28 days until Pokémon Sword & Shield release!

Now there’s a pretentious title if ever I wrote one.

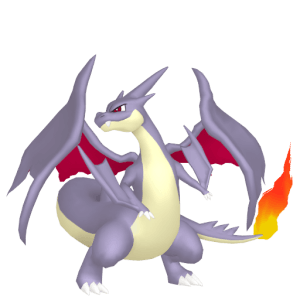

It’s no secret that the British Industrial Revolution was part of the inspiration for at least some of the Pokémon, locations and themes of the upcoming games. Galarian Weezing’s design is a clear reference to both the smokestacks of coal-burning furnaces and the stereotypical fashion of 19th century England (see also my colleague Nick’s recent article on that classy devil of a Pokémon).

One of the major cities of central Galar, from what we’ve seen, appears to have aesthetics pretty heavily informed by the Industrial Revolution, all brick and iron and steam. And the developers have been nice enough to give it to us explicitly: game director Shigeru Ohmori, in an interview with US Gamer, referred to Britain’s role as the cradle of the Industrial Revolution as part of the inspiration for the themes of ambition, “strength and greatness” that the team wanted Sword and Shield to evoke.

All of that… well, makes sense. The 19th and early 20th centuries were the height of Britain’s power; the British Empire was the largest and most technologically advanced state in the world, with the biggest economy and the greatest military might. You can’t create a Pokémon region based on Great Britain and not somehow use the Industrial Revolution.

So, if this choice so obviously makes sense, why do I need to write an article about how it’s actually a really significant decision that might say something important about the themes and underlying beliefs of Generation VIII’s stories?

Partly it’s because I’m struck by the way Ohmori specifically singled out the Industrial Revolution in his comments in that interview. There are plenty of other interesting eras of British history, and some of them are clearly at work in the design of areas and Pokémon in Sword and Shield, but it’s the Industrial Revolution in particular that we’ve been “told” to look to when we try to understand these games. Even without that hint, though, the 18th and 19th centuries stick out to me, probably more than any other period of British history, as a fascinating choice because of what Pokémon is – a fantasy Voyage of the Beagle – and what its stories are about – the relationship between humanity and nature.

Pokémon’s core game mechanics – the process of catching Pokémon, documenting them in the Pokédex, building up an exhaustive collection and learning about their abilities and evolutions – are about the human mania for documenting the natural world. Every Pokémon fan who goes far enough down the rabbit hole eventually hears the story of Satoshi Tajiri’s childhood hobby of insect collecting, one of several hobbies that take us out into nature and encourage us to break bits off of it, so we can examine them, categorise them and understand how they work. It’s part of the games’ most basic appeal, the way they provoke the thrill of discovery and the feeling of having mastered a complex body of knowledge through investigation. Remember what Professor Oak told us, all those years ago? We’re going to go out into this wild region we’ve never seen before and document everything we find there, as part of a grand new project in the history of science, something that will change the way we understand the world.

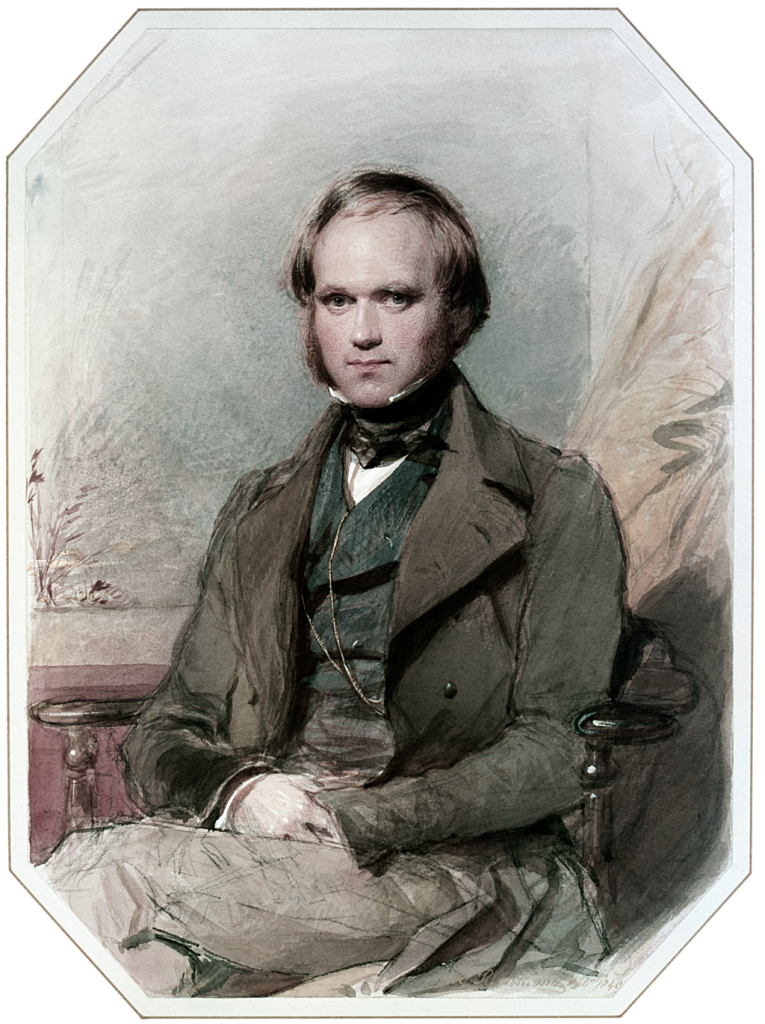

That theme matters, because the same period of history that saw the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the 18th and early 19th centuries, was also the age of Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, the naturalists who first outlined the theory of evolution by natural selection. They were Pokédex writers, exploring unfamiliar regions and trying to understand the fantastic, almost magical things they saw there. It was the age of Mary Anning, Richard Owen and other English pioneers of palaeontology, who introduced the scientific community to the concept of dinosaurs. And of course, because Pokémon can be not just animal or vegetable but mineral too, I would be doing a great disservice by not mentioning James Hutton and Charles Lyell, the Scottish geologists whose work paved the way for the theory of evolution by showing that the Earth’s continents were shaped gradually over millions of years, not in sudden catastrophes (or, uh… by the tantrums of cosmically powerful legendary Pokémon). This is when humanity’s understanding of nature changed forever.

And you might very well say “but Chris, you colossal nitwit, Game Freak won’t have put enough thought and care into their worldbuilding for any of this to matter!”

However, I think they do care about their regions reflecting what’s distinctive and important about the corresponding locations in the real world, or at the very least have started to, because Alola wouldn’t be Alola if it weren’t also Hawai‘i. Characters like Hau and Hala speak using Hawaiian idioms. Oricorio symbolises modern Hawai‘i’s blending of Polynesian, North American, Iberian and Japanese culture. The four Tapu correspond to the four great gods of the ancient Hawaiian religion, the warlike Kū, life-giving Kāne, beneficent Lono and mysterious Kanaloa. Gumshoos and Alolan Raticate re-enact the drama of the introduction of the Asian mongoose to Hawai‘i. Bruxish and Comfey are both based on famous emblems of Hawai‘i. The Ultra Beasts are explicitly a riff on the concept of invasive species, which are particularly devastating to isolated island ecosystems like Hawai‘i. Hau’s obsession with malasadas, for goodness’ sake. But most importantly, the whole Trial system and the greater influence it allows Pokémon to wield over humans are a gesture to the idea of “oneness with nature” that characterises all kinds of stereotypical depictions of indigenous societies.

And that brings us to why Galar and Alola have to be different.

Pokémon’s stories are about the balance between humanity and nature – sometimes explicitly pitted against one another, as in both Black and White and Alpha Sapphire and Omega Ruby. The anime will regularly have humans, in perfect innocence, mess with the lives of Pokémon (or vice versa!) without understanding the consequences of their actions, so that Pokémon trainers – people whose special skills allow them communicate with both sides – must intervene to restore balance.

Pokémon presents us with a vision of a world where humans are the responsible stewards of the natural order, using advanced technology to protect the environment and live in harmony with it. It’s essentially (in my opinion) the creators’ aspirational vision of what humanity’s position in the real world should be as well. Most of Pokémon’s top-line villains are people who somehow mess with that. Maxie and Archie disrupted the balance of nature and civilisation by trying to take sides, N thought the balance was unjust and wanted to upend it, Lysandre didn’t trust humanity to maintain it, and Lusamine thought she was the only one who could. Even within the setting, though, there are multiple legitimate perspectives on how that balance should work.

Alola, taking cures from (a simplified, pop-culture understanding of) indigenous Hawaiian society, sees humans as part of nature, ultimately beholden to nature. Trainers in Alola have their competence certified primarily by powerful wild Pokémon, not by other trainers, and the human trainers who oversee that process, the four Kahunas, are chosen by the legendary Pokémon of the region who represent the will of the islands themselves.

Contrast that to a region based on Britain, perhaps with a special focus on the Industrial Revolution. That region cannot have the same perspective; it wouldn’t make any thematic sense. Given what we already know, without actually seeing the games or the new series of the anime (although it sounds like that will not actually take place in Galar, or at least not exclusively) I would expect generation VIII to instead take a stance influenced by the atmosphere and philosophy of 19th century Britain. This was a period when serious thinkers believed we were close to solving science, for good – that there were probably only a handful of major questions left in physics and chemistry, and finishing up biology would just be a matter of documenting every species (and how hard could that be, as the Pokémon trainer said after completing the Kanto ‘dex).

Scientific thought in this period revels in the completeness of human understanding of, and power over, nature – and, frankly, you can see why. During the Industrial Revolution, humans started altering and controlling our environment far more than we ever had before.

Steam power revolutionised transport, bringing the whole world closer together; the mechanisation of agriculture and superior understanding of crop rotation allowed fewer people working on less land to produce more food; agriculture in turn was replaced by manufacturing as the primary occupation of most ordinary people in Britain, shifting society from a dependence on nature to a dependence on technology. And, of course, we started burning more and more fossil fuels every year – we’re still figuring out what the long-term effects of that one will be.

If Alola’s spiritual heritage is one of harmony with nature and humility in the face of ancient powers of the Earth, Galar’s is one of mastery of nature, soaring ambition that harnesses natural forces to change the world. That’s the theme I’m going to have on my mind when I play games and watch anime episodes set in Galar. Whether that’ll actually help me to get at any deeper meaning… for now, let’s just say time will tell.

Do I have a good point? Am I reading too much into this? Am I essentially the Pokémon community equivalent of a raving homeless drunkard yelling about aliens from a street corner? The answer to all these questions and more is “yes,” and we all look forward to hearing which questions you’ll answer “yes” to, in the comments below and on our Discord!